Summary

I have argued for some time that a robust recovery will occur after households adjust spending downwards. I believe that households must adjust spending down to reflect levels of lifetime wealth that are lower, after the global financial crises of 2008-2009, than had been expected prior to the crisis. Another way to say the same thing is that households need to adjust their savings upwards to accomplish a long-term deleveraging and readjustment of debt levels

The data show that such adjustment may be starting to occur. This is good news and bad news. The good news is that it will allow a robust recovery. The bad news is that it implies there will be a recession, potentially a bad recession, before that recovery can occur.

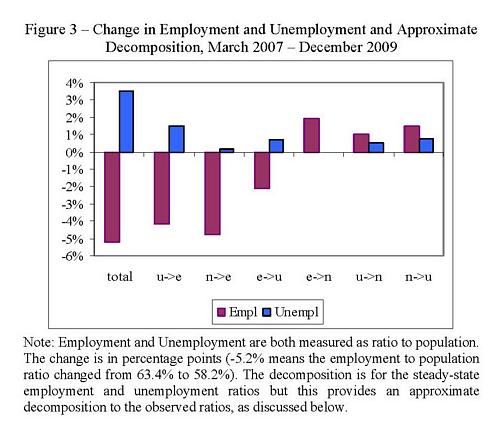

The 2008-2009 recession and the current recovery are all about households de-leveraging and adjusting spending levels downwards relative to income. There are, however, key aspects of the recent past that are often neglected or misunderstood:

- Starting in 2008 the “Savings rate” rose, particularly after the crisis hit in late 2008.

- But, the rise in the savings rate from 2008-2010 was almost entirely due to changes in taxes and almost not at all due to changes in household behavior. (See the discussion below on the difference between savings as percent of personal income versus disposable income.)

- For 2011 the reverse has been true – changes in household behavior

Note that any rise in the “savings rate” due to lower taxes is not really an adjustment in household behavior or overall debt profile. Increased government debt will eventually have to be repaid through future higher taxes.

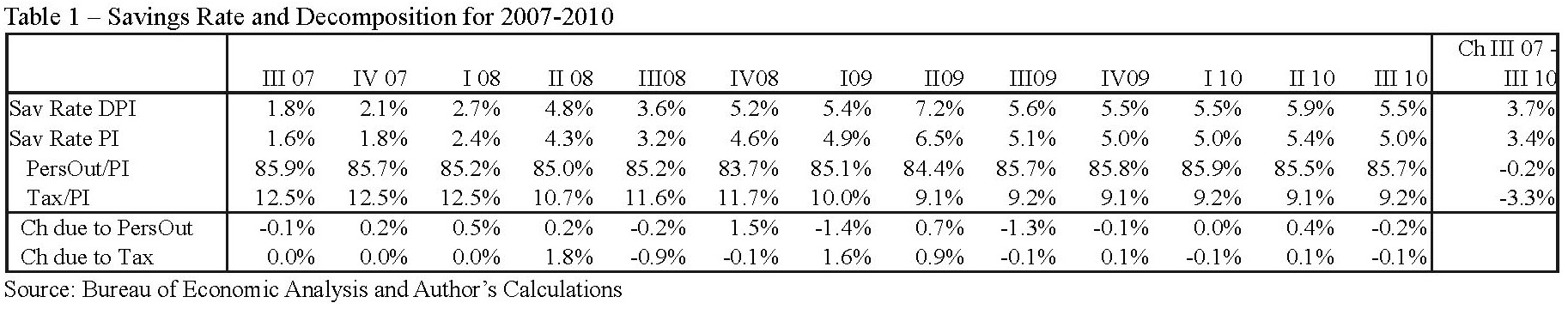

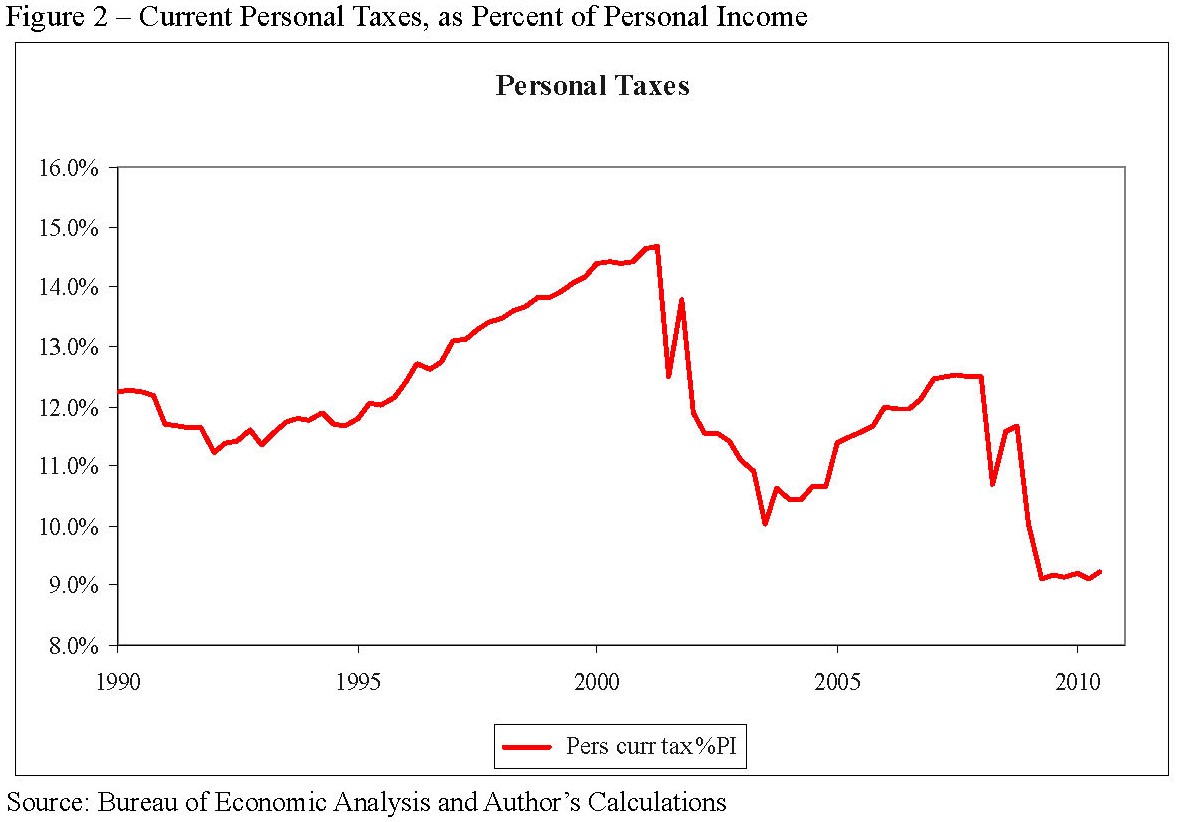

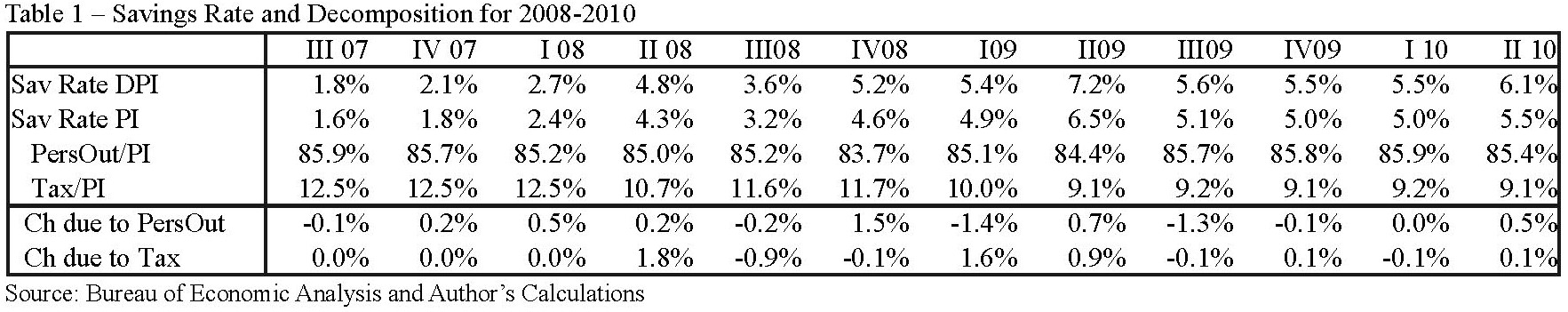

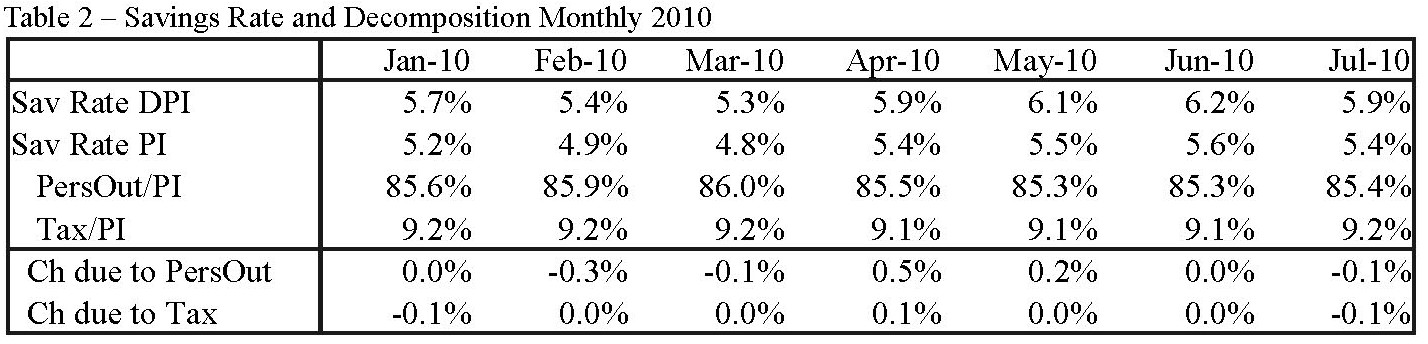

Table 1 shows the current savings rate and spending rates (quarterly) during and subsequent to the recession. A few points to note:

- During 2008-2010:

- The savings rate (as percent of personal income – see discussion below) rose by 2.5 percentage points

- Of this 2.5 percentage point rise, 2.6 percentage points was due to lower taxes

- During 2011 so far (admittedly only two quarters)

- The savings rate has been almost unchanged

- Spending fell by 0.7 points, taxes rose by 0.8 points

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis and Author’s Calculations

If, as I think will happen, households continue to adjust spending down and taxes rise modestly, there will be a recession. This will, however, set the stage for a robust recovery to follow.

Since the bubble burst in 2007-2008 all forms of wealth have fallen – falling housing prices have reduced real estate holdings; stock markets have fallen or stagnated; and, probably most importantly, employment and prospects for future earnings have fallen. The fall in lifetime wealth should naturally induce some adjustment in household spending. The recession was simply that adjustment of spending to new levels of perceived wealth.

I don’t think the imbalances that led to the financial crisis of 2007-2009 are fully redressed (at least in the US). Spending is supported by low taxes (an explicit government policy to ameliorate the recession of 2008-2009). Eventually taxes will have to rise to fund the government deficit, and this will put pressure on spending. Either the savings rate will fall (building future imbalances) or spending will fall (recession).

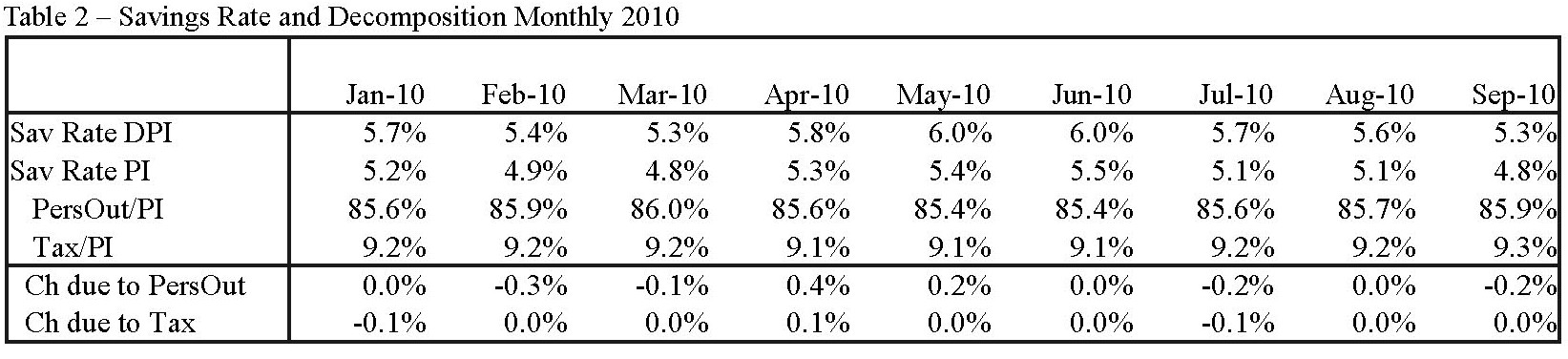

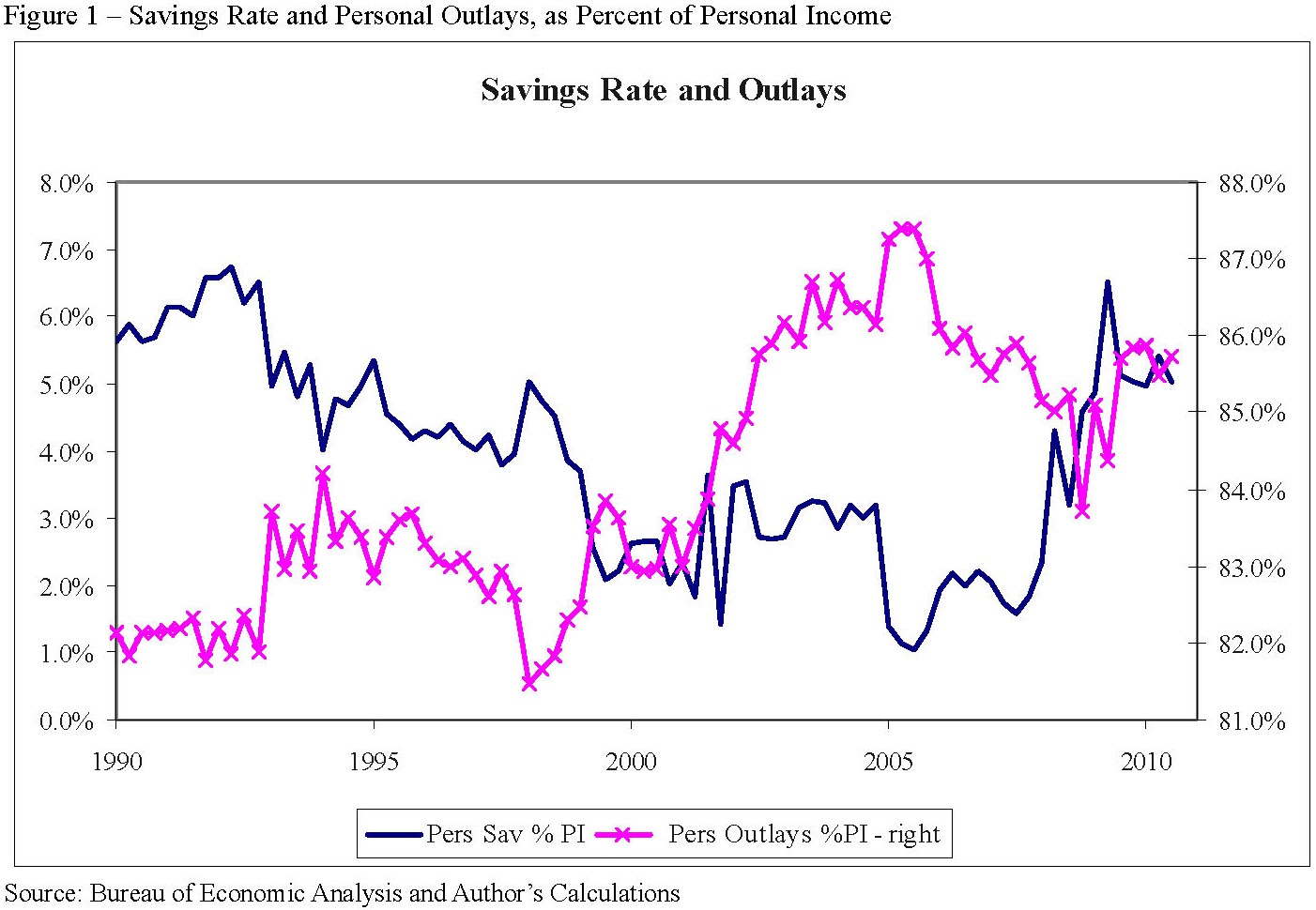

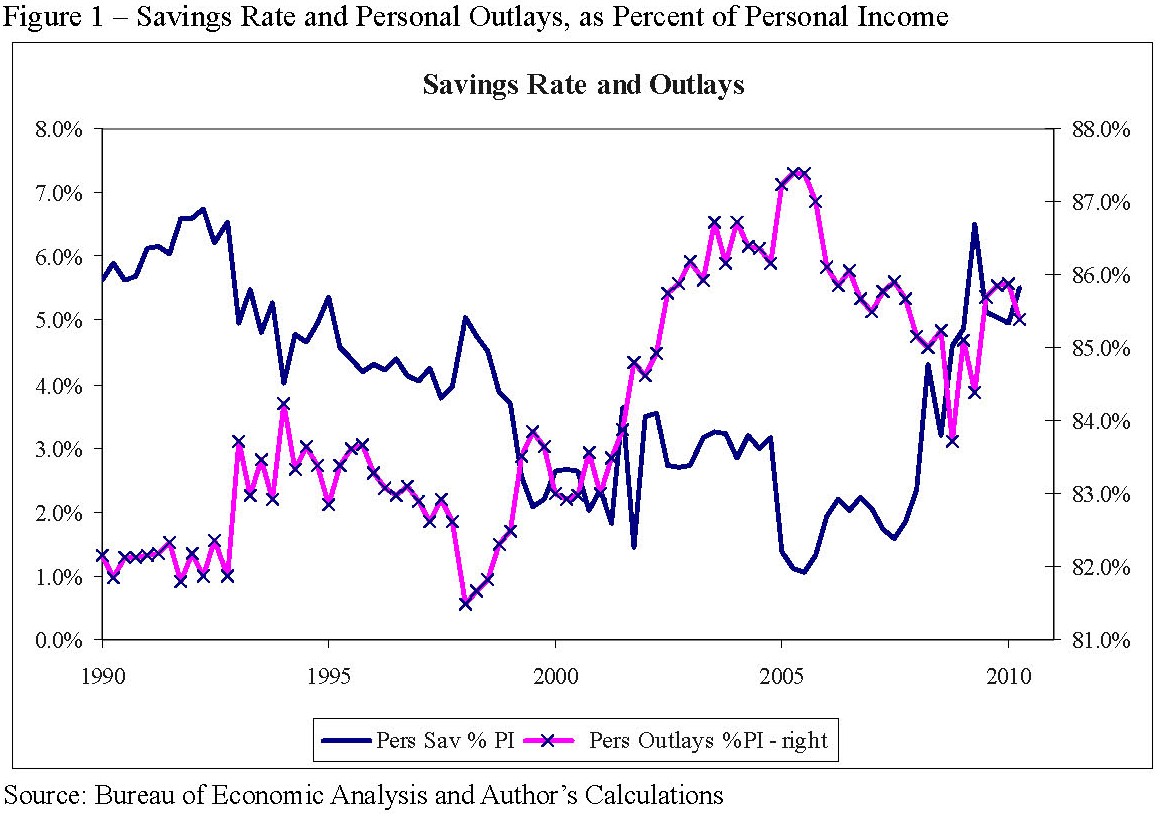

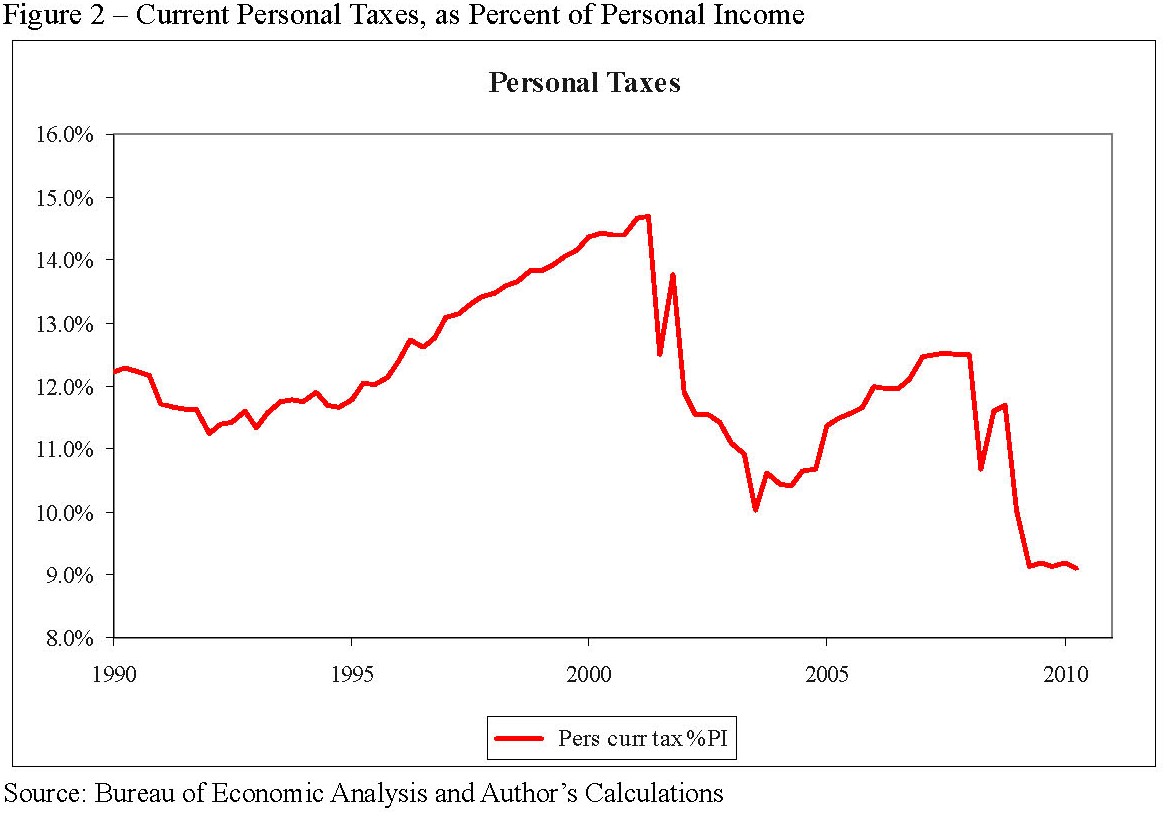

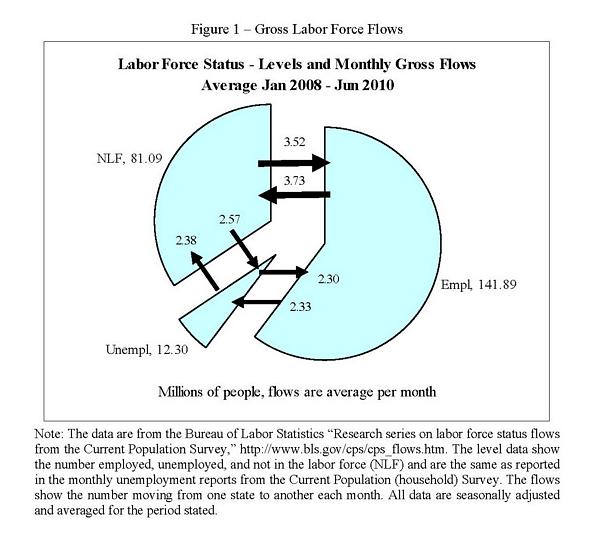

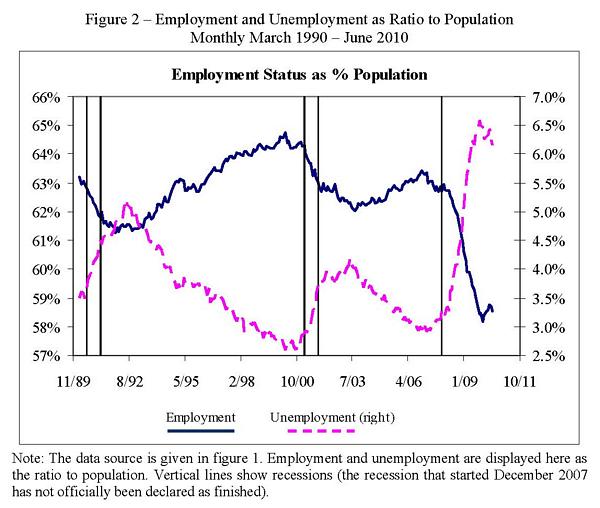

Longer-term trends (over the past two decades) are shown in figures 1 and 2:

- Savings rate (more accurately, what is left over from current spending) fell from roughly 6% of income to below 2% in 2007/2008 and has now rebounded to almost 6%.

- Taxes rose during the late 1990s but fell dramatically post-2000, and again in 2008/2009.

- Spending has risen from about 83% of income (1990s) to over 87% in 2005 and is now roughly 86%. It is still high by historical standards and supported by low taxes, even if not as high as during the bubble.

Household debt (measured in the Federal Reserve’s quarterly flow of funds reports) has fallen since early 2008, from 96.4% of GDP in QI 2008 to 93.6% in QIV 2009. This is good news and shows households have started de-leveraging. Unfortunately the increase in government debt has been far larger. According to the OECD, central government debt for the US grew by $2.5tn from 2007 to 2009, or from 35.6% of GDP to 53.1%. Future tax liabilities, which are a future liability and thus function as a sort of implicit household debt, have probably offset any decrease in directly-owned household debt. The net result is that household leverage has probably not decreased much, if at all, over the past three years.

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis and Author’s Calculations

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis and Author’s Calculations

Decomposition of Movements in Spending and the Savings Rate

Table 1 shows the savings rate. The definitions of savings and spending rates, together with a decomposition of savings as a percent of personal income, are discussed here.

Economists commonly consider the “savings rate,” which is the difference between current income and spending – the excess of income left after spending and taxes are accounted for. The definition is:

Savings Rate = (Disposable Personal Income – Personal Outlays) / Disp Pers Inc .

(This “savings rate” is not exactly savings as one usually thinks of savings, but rather a definition of the excess of income over spending in the aggregate economy. One could equally well talk of the “spending rate” – Outlays / Income – which is just one minus the “savings rate”.)

It is useful to decompose the rise in the savings rate in order to understand it a little more. To do so it is useful to consider savings as a percent of total personal income. Basically,

Disposable Personal Income = Personal Income – Personal Current Taxes

Savings = Disposable Personal Income – Personal Outlays

The standard definition of the savings rate is savings divided by Disposable Income:

Savings Rate (DPI) = (Disposable Personal Income – Personal Outlays) / Disp Pers Inc

= 1 – Personal Outlays / Disp Pers Inc

We can, however, define a savings rate divided by personal income that is only slightly different:

Savings Rate (PI) = (Personal Income – Personal Current Taxes – Personal Outlays) / Pers Inc

= 1 – Pers Curr Taxes / Pers Inc – Pers Out / Pers Inc

Since DPI and PI differ only by Pers Curr Taxes, which has monthly changes that are not large relative to the level of DPI and PI, the two measures will be very much the same. The advantage of the second is that we can decompose changes in that savings rate into changes due to taxes and that due to changes due to outlays (spending).