Summary

July personal income figures released today show an increase in spending relative to income. This is not good news because the higher spending means savings rates are down and household de-leveraging and spending adjustments are not proceeding. Furthermore, revisions for the first and second quarter show higher spending than previously reported, implying that adjustment is occurring less fast than previously estimated.

In my view a robust recovery will occur when (and if) households have finished adjusting their spending to new, lower, levels of lifetime wealth. The 2008-2009 recession and the current recovery are all about households de-leveraging and adjusting spending levels downwards relative to income. I believe households still have some way to adjust, and perversely government stimulus (implemented to ameliorate the impact of the recession) may have simply delayed the process. Yes, savings rates have recovered dramatically from the lows of 2007. But most of the rise in savings rates has been due to tax cuts rather than lower spending. At some point taxes will have to rise to address fiscal imbalances, and households will likely adjust down spending in response.

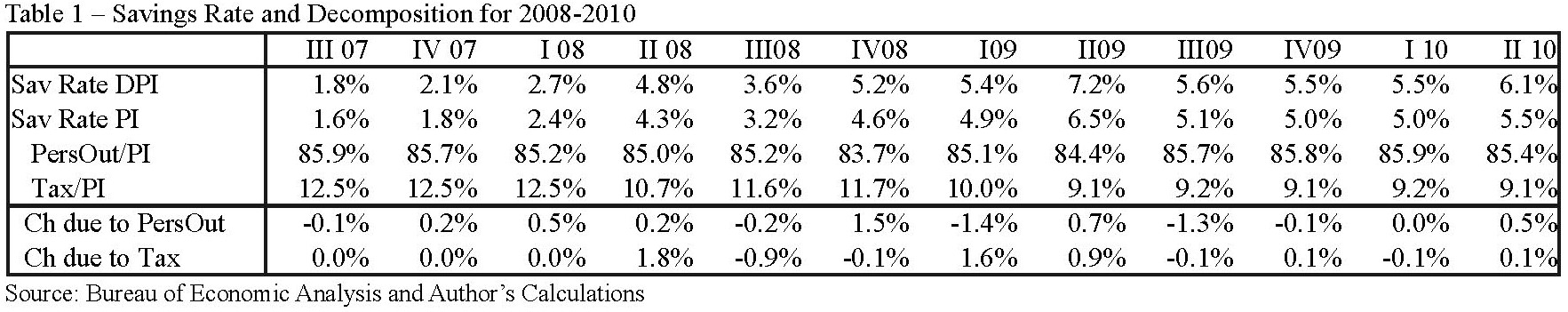

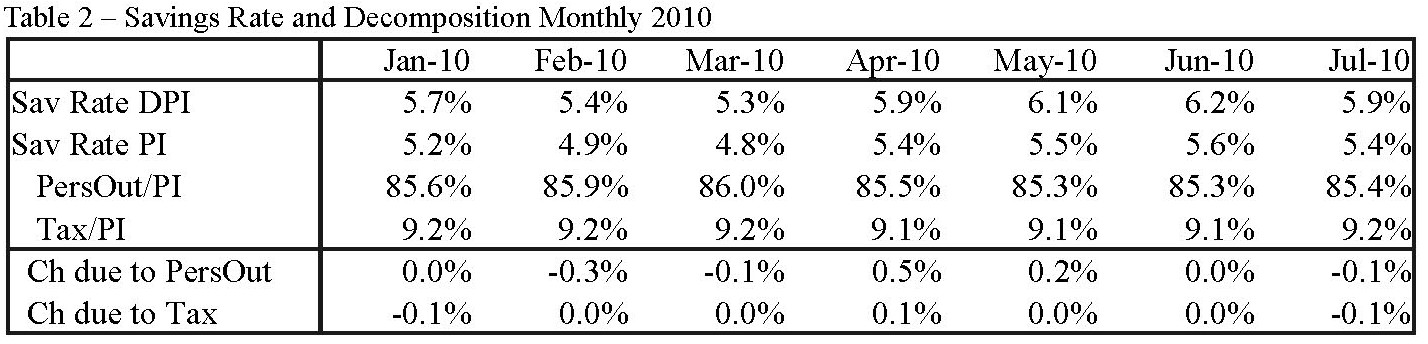

Table 1 shows the current savings rate and spending rates, quarterly. The savings rate for the second quarter of 2010 is dramatically higher than for 2007, but almost all of the change in savings rate has been due to falling taxes rather than lower spending. Table 2 shows monthly figures, with July personal outlays as a percent of income rising slightly and savings rates falling.

There is no doubt trouble stored up for the future. Since the bubble burst in 2007-2008 all forms of wealth have fallen – falling housing prices have reduced real estate holdings; stock markets have fallen or stagnated; and, probably most importantly, employment and prospects for future earnings have fallen. The fall in lifetime wealth should naturally induce some adjustment in household spending. The recession was simply that adjustment of spending to new levels of perceived wealth.

I don’t think the imbalances that led to the financial crisis of 2007-2009 are fully redressed (at least in the US). Spending is supported by low taxes (an explicit government policy to ameliorate the recession of 2008-2009). Eventually taxes will have to rise to fund the government deficit, and this will put pressure on spending. Either the savings rate will fall (building future imbalances) or spending will fall (recession).

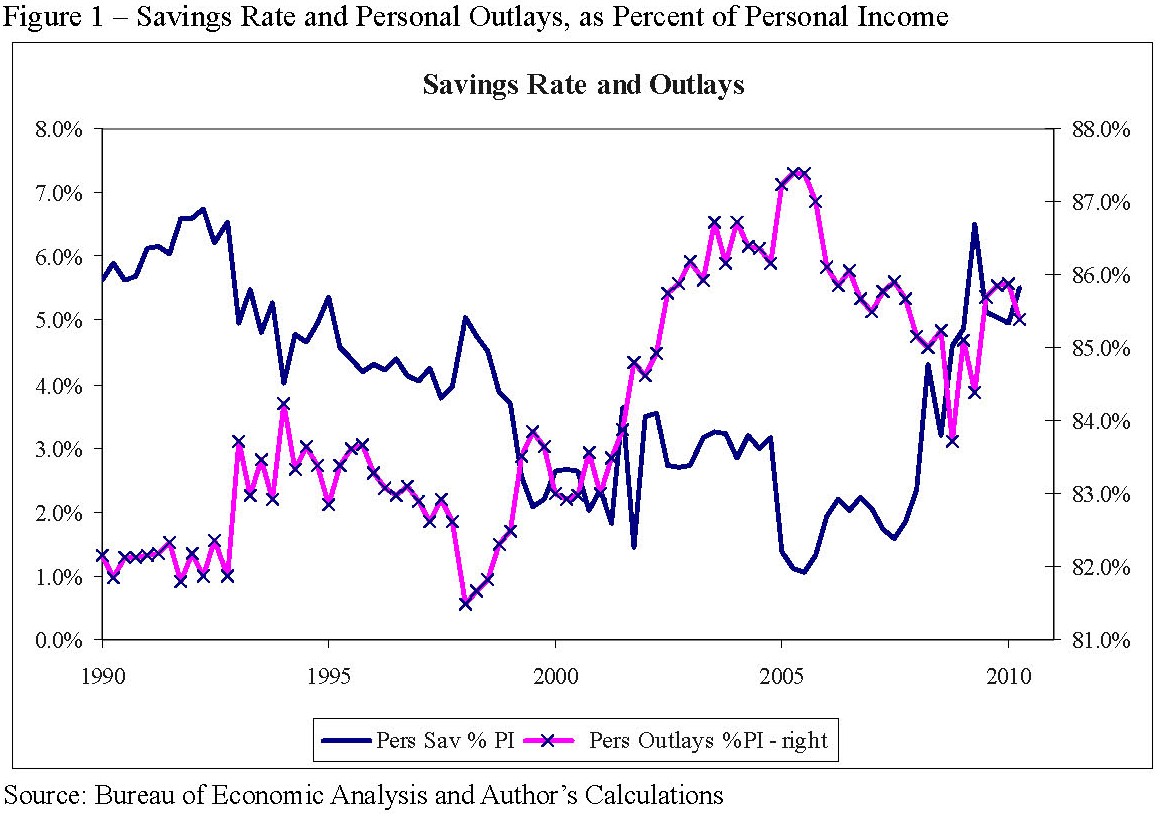

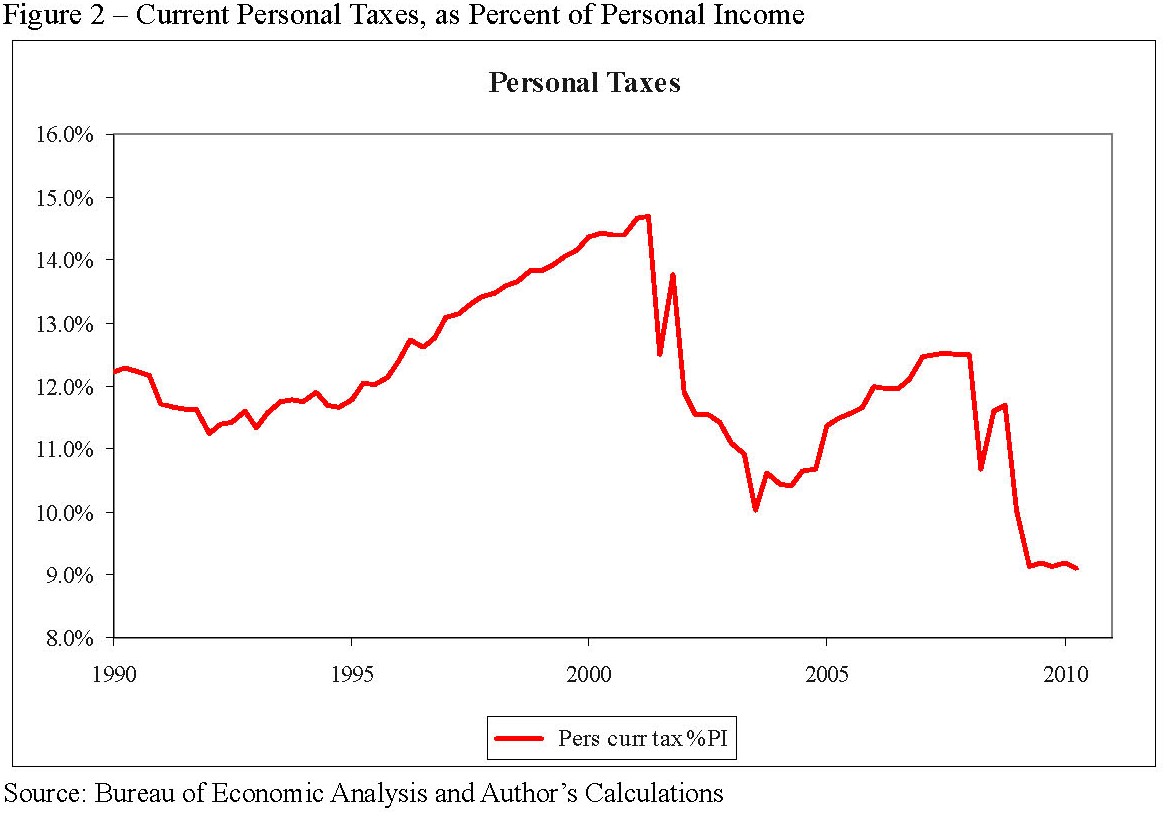

Longer-term trends (over the past two decades) are shown in figures 1 and 2:

• Savings rate (more accurately, what is left over from current spending) fell from roughly 6% of income to below 2% in 2007/2008 and has now rebounded to almost 6%.

• Taxes rose during the late 1990s but fell dramatically post-2000, and again in 2008.

• Spending has risen from about 83% of income (1990s) to over 87% in 2005 and is now roughly 85%. It is still high by historical standards and supported by low taxes, although not as high as during the bubble.

Household debt (measured in the Federal Reserve’s quarterly flow of funds reports) has fallen since early 2008, from 96.4% of GDP in QI 2008 to 93.6% in QIV 2009. This is good news and shows households have started de-leveraging. Unfortunately the increase in government debt has been far larger. According to the OECD, central government debt for the US grew by $2.5tn from 2007 to 2009, or from 35.6% of GDP to 53.1%. Future tax liabilities, which are a future liability and thus function as a sort of implicit household debt, have probably offset any decrease in directly-owned household debt. The net result is that household leverage has probably not decreased much, if at all, over the past three years.

Decomposition of Movements in Spending and the Savings Rate

Table 1 shows the savings rate. The definitions of savings and spending rates, together with a decomposition of savings as a percent of personal income, are discussed here.

Economists commonly consider the “savings rate,” which is the difference between current income and spending – the excess of income left after spending and taxes are accounted for. The definition is:

Savings Rate = (Disposable Personal Income – Personal Outlays) / Disp Pers Inc .

(This “savings rate” is not exactly savings as one usually thinks of savings, but rather a definition of the excess of income over spending in the aggregate economy. One could equally well talk of the “spending rate” – Outlays / Income – which is just one minus the “savings rate”.)

It is useful to decompose the rise in the savings rate in order to understand it a little more. To do so it is useful to consider savings as a percent of total personal income. Basically,

Disposable Personal Income = Personal Income – Personal Current Taxes

Savings = Disposable Personal Income – Personal Outlays

The standard definition of the savings rate is savings divided by Disposable Income:

Savings Rate (DPI) = (Disposable Personal Income – Personal Outlays) / Disp Pers Inc

= 1 – Personal Outlays / Disp Pers Inc

We can, however, define a savings rate divided by personal income that is only slightly different:

Savings Rate (PI) = (Personal Income – Personal Current Taxes – Personal Outlays) / Pers Inc

= 1 – Pers Curr Taxes / Pers Inc – Pers Out / Pers Inc

Since DPI and PI differ only by Pers Curr Taxes, which has monthly changes that are not large relative to the level of DPI and PI, the two measures will be very much the same. The advantage of the second is that we can decompose changes in that savings rate into changes due to taxes and that due to changes due to outlays (spending).

Figure 1 shows the longer trends in the savings rate and outlays – the savings rate has been trending lower for the past couple decades but with a sharp rebound starting in 2008. Spending has increased, with a particular jump about 2001. Figure 2 shows personal current taxes. This fell starting 2002 (the George W. Bush tax cuts), and then again starting in 2008 (in response to the recession). Taxes will no doubt rise at some point, in response to substantial government deficits.